Edward P. Clapp

by Swara Shukla · Published · Updated

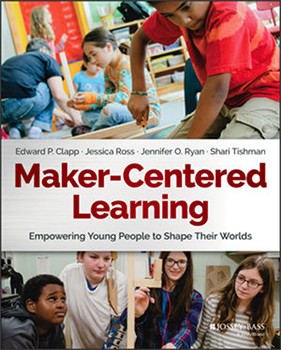

Edward Clapp is a Principal Investigator at Project Zero interested in exploring creativity and innovation, design and maker-centered learning, contemporary approaches to arts teaching and learning, and diversity, equity, and inclusion in education. In addition to his work as a researcher, Edward is also a Lecturer on Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Edward’s most recent books include Participatory Creativity: Introducing Access and Equity to the Creative Classroom and Maker-Centered Learning: Empowering Young People to Shape their Worlds.

Edward also holds an MLitt in Creative Writing from the Universities of Glasgow and Stratchlyde in Scotland.

Depends on who you ask. Some people would definitely say that you are a creative idea because it took special thought; you are atypical, out of the so-called “ordinary”. You are not a regular cat that you might meet up in The Highlands but a very special cat who is blue and likes horses and has a quill-shaped tail.

A lot of other people would also say that you are not a creative idea but just a quirky one – a little bit outside the ordinary. For them you are who you are, you have all these interesting characteristics in your personality. But you don’t really change anything in what they might call a “domain” – in a field of practice or in a culture in some sort of way. You are quirky within that domain or field of practice or culture.

So what your question asks is to push for a definitive answer in a Big C vs Small c way. Theorists that adhere to “Big C” creativity theory use metrics along the lines of eminence and impact on the domain to suggest what is or is not creative, whereas those that believe in “Small c” creativity theory see those quirky, outside the box creations as being creative themselves.

So, it really depends on who you ask. And I know, I know – you are asking me!

I think my position on this is I understand both perspectives and don’t attempt to come down on the side of either one of them. I think whether you take the Big C perspective on creativity and see it in terms of an impact on a domain, or whether you take the Small c perspective on creativity and see these quirky moments and aberrations as being creative; any one of them requires thinking and an approach to developing ideas that is both distributed and participatory, perhaps on different levels. But participation and distributed cognition or distributed creativity are necessary for either one.

I am going to politely not answer the question, by saying: Yes, you are a creative idea; yes, you are a quirky idea. No, you are not a creative idea; no, you are not a quirky idea!

Okay, let’s say you are walking around in the mountains in Inverness or Aviemore. You’re by yourself, with your thoughts, and then you run back to your cosy cat-bed and sit down to write down ideas and turn them into poetry. It might appear that you’re doing this all by yourself; but in reality, what’s happening is in those moments of reflections – when you’re drawing upon your past experiences – you’re collaborating with other cats and other people that you’ve interacted with in the past. You didn’t entirely live in the Highlands all by yourself, you grew up there and interacted with so many other cats and humans. Any reflections, thoughts or ideas that emerge for you are in some way collaborations with all these cats and humans that you have engaged with in the past. That’s one way to think about it.

The other way to think about it is that you are engaging with the environment while out on the walk; you might see a brook, a creek, snow or some pine trees. If you go back and write about the creek, the brook, the snow and the pine trees, you’re collaborating with the environment. The environment itself is a part of that participatory process. You may be the Vehicle, or the Lead Player in that poetry writing experience, but it is also important to remember and look at who the other actors are in that experience; those would include actors from your current and past lives (and experiences) and actors from your immediate environment that you’re responding to.

There is no isolation; there is always an interaction either with the environment you’re in or the environment you’ve been in in the past.

I think that whenever groups of people share work – whether face-to-face or in a natural environment – they are naturally building off of one another’s ideas. So, if you and I were in virtual creative writing experience, and I was sharing poems and you were sharing poems, then quite explicitly – and implicitly, even – the next poem I write after reading yours, and the next poem you write after reading mine would be somewhat influenced by the other. As people come together, they share work and perspectives, challenge one another and give one another feedback. In doing that, we aid one another not just in developing as poets, but also as participants in the process of building and voicing creative ideas.

So, I would think that’s one way that a virtual creative writing environment naturally supports participatory creativity. Another way is if you think that each person who participates in that virtual network plays a different role, and it might look like they are playing the same role – poets – but someone might play the role of a sceptic, or a cynic, or science fiction specialist, or limerick master. As people bring different aspects of their work to that and play these different roles, they are supporting each other in developing participatory creativity.

Yes, there is an origin story to all of this. It’s funny; a bunch of students at High School were interviewing me recently, and they went: “you’re talking about Participatory Creativity, but you know it’s just your name on the book! You know, you make it look like you’re the sole author!” They really got me in a corner there. But I think being an author, being a writer for something is a bit different from participating in the process of developing the idea. I think that I’m just bringing voice to a concept that many actors have contributed to.

In that vein, some of the seeds for this for me were planted while I was at residence in a Doctoral Programme at Columbia University. I was there for one year. During that time, I worked really closely with a creativity instructor named Michael Hanchett Hanson; he was really interested in pushing ideas around towards a socio-cultural approach to creativity. This came out of his mentor – a creativity theorist named Howard Gruber. So, during my time there, we had these discussions and sessions where we pushed the envelope of what a more distributed and socio-cultural view of creativity might look like. And it was then that the first seeds of thinking about participation started to emerge.

I sat with that for a while. When I later finished my doctoral studies at Harvard, I was working on my dissertation and was prompted by a professor there, who said the way to really make an impact within academia or anywhere is to come up with concepts you can name. When you start to name things, they start to have traction in the world. I started to think in that direction. I was working closely with another graduate student at the time and she really understood these concepts. She and I would share ideas; and while working with her, we came up with the idea of Participatory Creativity as being a good name of this kind of framework. I was also working with a writing group while I was developing the book, and within that writing group was a woman who was originally from the Midlands, I think – she hated the name “participatory creativity” because her English accent pronounced it differently than my American accent; she actually added another syllable, so she thought it sounded too clunky!

So that’s a bit of the origin story behind the idea, but also of course it connects to the ideas of other theorists like I have mentioned. My framing of participatory creativity is a synthesis of all that.

Yes, of course! During my postgraduate experiences in Scotland; we put up a spoken word poetry CD – look it up if you get a chance to prowl out on the streets of Glasgow – called Spoke. It should be in the Glasgow University library or the Edwin Morgan centre. I produced that with a bunch of other people, I can’t say I made it because lots of people made it. And that was certainly a community.

I think in a community, many people have different voices that they can contribute to a common idea. We were working on this common idea of the spoken word, a spoken storytelling event, and poetry; and we were purposefully looking for people who could bring a variety of perspectives to that work. That’s the case when any group of people comes together to support a creative endeavour. Whether that’s making a work of theatre or making a work of creative writing; people bring different perspectives and different aspects of themselves and everyone benefits from those.

You always play a role if you choose to. You don’t need to write in order to provoke, to evoke, to prompt others to write. In many ways when something difficult needs to be said or somebody needs to be assuaged – that could be the work that you need to do! And that is very important work in the writing process. You can play a myriad of roles while swishing your tail!