Dr. Jonas Ridderstrale

by Swara Shukla · Published · Updated

Dr. Jonas Ridderstråle is one of the world’s most influential and respected business thinkers and speakers. In 2014, the Global Top 30 Management Gurus ranking put him at number 23 worldwide and among the top 5 in Europe. He is the author of international bestsellers such as Funky Business, Karaoke Capitalism and Re-energizing the Corporation.

The book was conceived, written and launched in a day and age when it was becoming clear that power was in the process of being transferred from those who controlled the financial capital to those who controlled the intellectual capital – “The Nerds”, basically! And our subtitle, Talent Makes Capital Dance, was kind of a metaphor to capture the fact that suddenly the discussion was very much the reverse; talented employees could exert a lot of power in relation to their employers when historically it was the other way around.

Back when I was doing academic research, I attended a dinner party, where someone turned to me to ask what I do. As soon as I told them that I did research in Business Administration, that someone turned around and started talking to someone else (laughs)! They were so convinced that the most boring thing on Planet Earth was research, especially in Business Administration! But it was becoming increasingly clear to us that not only did businesses have to become “funky” – unconventional times called for unconventional managing, leading, strategising and organizing – but also, as an effect of the measures taken by the likes of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, we had not just deregulated the economy, but deregulated life for ourselves and our kids. There was a lot of responsibility and freedom of choice ending up not just in the laps of select fews – the Fortune 500 or so CEOs – but with teachers, nurses, doctors, people working in the medical field, in the retail store. These individuals had to arm themselves with the most lethal and competitive weapon of the time – knowledge. So Funky Business was very much an effort to write a “people’s business book” that was not just relevant to those who had spent 25 years in the academic trenches or those who had reached the position of Senior Executives.

As for the “funky business”: people were absolutely convinced that business at the time shouldn’t be or wasn’t “funky”. It was expected to be male, middle-aged, pinstriped suits, clean white shirt and a tie – and it was supposed to be boring. We wanted to say that boring business did not stand a chance because it does not have the ability to attract and retain talent; and it does not create workplaces that ooze of inspiration, engagement and commitment. Clearly the era of business as usual was coming to an end. Enter business unusual. My co-author Kjell’s then-wife was a musician; and at their dinner-parties, they always talked about how music needed to be “funky”. We picked that little piece from the world of music and mixed it with our knowledge from the world of business and it became “Funky Business” – which I guess to most people is an oxymoron!

Someone else translated it into Swedish. The book itself was conceived in Swedish and written in English, which made the translation back into Swedish quite easy! Whenever the translator translated a chapter and called me to discuss it, I used to keep going “no, this is supposed to be that in Swedish.” I also gave speeches in Swedish, so I knew exactly what and how I meant to express something. The second book, Karoake Capitalism, was conceived in English and written in English – which made the translation into Swedish much more difficult.

In the process of doing all the speeches between Funky Business and Karaoke Capitalism, I started to think more in English than in Swedish. I think it’s also quite interesting to mention that I started noticing that the language in which you think has an impact on the creative process. My thoughts developed in slightly different ways when I was thinking in English rather than Swedish. One very simple example would be that it’s a whole lot easier to do alliterations in English than in Swedish – the title Karaoke Capitalism being a case in point – simply because there are so many more words to choose from! So, the interrelation between language and creativity, I think, is very interesting to look at. But, I am getting derailed now!

In fact – I AM MAXIMUS!

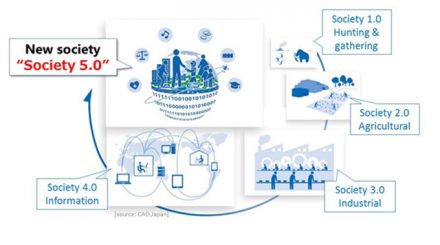

My little academic answer would be – it depends. I think it varies over time. If we go back to the industrial era – particularly the 20-25-year period preceding the shift into the information society – the challenge for most companies was to perfect the “known”, to become marginally better at what they were already pretty darn good at. You didn’t need a lot of creativity because the focus was much more on efficiency – to squeeze out the extra 10%, 15% or maybe towards the end, 2% of productivity and efficiency from your organisation. With the new era, however – the Information society or the Knowledge society, whatever you prefer to call it – the main challenge shifted. It was no longer a question of perfecting the known but that of creating the unknown. Innovation, of course, is all about creativity. Innovation not just in a technological sense; we also saw innovation of a new management model (meritocracy over bureaucracy), and the business model (favouring skill over scale and scope.)

This onus on creativity in the information age brought to the fore issues related to diversity; we know that Creativity = Diversity2.. Without diversity you don’t get creativity. This also had a major impact on what it takes to put together and lead a successful corporation. In the old day and age, diversity was not a good thing; if you don’t need creativity, and are only going for efficiency and productivity, diversity is not a good idea; because then you have debates and you have discussions and it takes a lot of time and you disagree and there is stuff going on!

If you need to innovate to create the unknown, however, you cannot survive without diversity; you need a constant influx and infusion of talent, ideas, and perspectives.

I do love blabbering about diversity (you and I have more in common than you would think, eh?) We have a lot of diversity in our workplace. There is this awesome Indian woman who has a beautiful accent (no, I haven’t been told to say that, these are my words) and she is so cool. But it’s me getting derailed now.

When I started out doing what I still do, I had this arguably naïve belief that we were going to see an increasingly homogenous world. So, I am quite struck by how great cultural differences still are. Not just the differences that you see in daily life – those I’d expected – but in the world of business. To give you a little example – the ideas we write about in Funky Business and our other books, are of course coloured by the fact that I live in a country that is an outlier. Sweden is strange. People here believe that Swedish culture is normal, like most Indian people believe that Indian culture is normal (as you might like to tell your Indian friend.) If you take all the cultures in the world, there would be some cultures that are probably very close to the mean. There are some “average” cultures. My culture certainly isn’t, we are extreme in terms of many different things. Since the ideas in Funky Business were created in a specific context, if I introduce these ideas to people around the world, we would of course face a veritable “immune system” that is made up of the values and attitudes given by their specific contexts.

For instance, what do you expect from a “Leader”? Let me give you an anecdote. I was doing some work in an Eastern European country about 5-6 years ago; we flew in the day before I was delivering my speech and I did a press conference. And these press conferences are often quite tricky, because there’s a TV answer that differs quite a bit from a magazine answer. It went pretty well. I asked the organisers what the journalists thought of it, and they told me “journalists tell us you are a very humble guy”. Now, I was quite flattered, because in Swedish culture being humble is a good thing. I realised later that being humble, in their context, wasn’t particularly a good idea for a management guru. They told me about inviting an American management guru a couple of weeks before and he had asked to have a guy walk in the front to open doors for him, because as a guru you don’t open doors. And I had told them in my culture that was more like being an asshole! (Excuse the language).

Jonas does a purr-fect imitation of the Eastern European accent!

The day after, I delivered my speech – and it was a long speech, about 4 hours. After I was done, we had a Q&A session. Back then I was dressed in a slightly “funkier” way than I am right now – I was wearing a black leather bracelet. Not only that, mind you. (laughs). And the first question I got was – “Professor professor, you wear a black leather bracelet. Why you wear a black leather bracelet?” And I just said, “well its kind of an image-enhancer isn’t it?” And I could immediately tell that the answer hadn’t gone down well with the audience; they expected something else from a leader. So, I referenced the opening scene in the movie Gladiator, going, “when I wear a bracelet, I feel a bit like Maximus!” I could see something had started to happen because this was more in line with their expectations of a strong and forceful leader. I decided to go for it and yelled, “in fact – I AM MAXIMUS!” And everyone started applauding and went “yes, you are Maximus, you are Maximus!”

I think you should always be sensitive to the fact that what you say is not necessarily what people hear. There will be a filter between the stimuli and the perception; and that filter will always change the message that you are trying to convey.

Is it a problem? No. I think, in fact, it is one of the enriching things about doing what I do. I get to learn more about the differences and see how we can reconcile those differences by being respectful and by listening to the arguments of the other person. I don’t believe that one culture is superior to the other; but if we look at what is happening in the world and the effects of institutional and technological changes, I think there are signs suggesting that the kind of culture I come from – the Scandinavian culture – is pretty apt at dealing with many of the challenges and exploiting many opportunities that the New World exposes us to. From that viewpoint, I’d say I’m lucky to be born in a cultural context that works well in a world of extreme uncertainty, ambiguity and a lot of change; and a world in which debate and discussion are more important that pointing your finger, your hand, your arm in a particular direction and just telling people what to do,

That’s my story of how I got into business. By not deciding.

I originally wanted to study history and archaeology because I wanted to be Indiana Jones. When I told him, my mother’s then-husband said to me, “so, you want to become a bus-driver?” Not that there’s anything wrong with being a bus-driver, but what he was saying was that I had top grades and was planning to use them to enter an occupation that you’d be stuck in if you realised you didn’t like it. One of the advantages of doing an MBA is that you don’t have to decide, you can do so many things with an MBA. You can probably even work in archeology! You won’t be the one digging, but you could perhaps arrange funding for projects to do it.

So, I decided not to decide. That’s how I got an MBA. When I got my MBA, I again decided not to decide, and got a PhD. After that, I decided not to decide yet again and stayed in research. I decided not to decide and wrote a popular management book. To this day, I am doing my very best not to decide.

The first two years of the MBA were extremely tedious and boring. Back then in Sweden, it was structured in a slightly different way; it was a four-year programme where you get your Bachelors and Masters degree together as a package. The numbers stuff wasn’t my thing; I appreciate it today after running my own business and having run my own training and development company. Back then, I couldn’t relate to it. My mum was a school-teacher. I didn’t come from a business background at all, we didn’t talk about that stuff over dinners.

When I started my MBA, I probably replaced Indiana Jones with Gordon Gekko from Wall Street. But I progressively began to understand that that was not my thing either. What interested me was human relationships. What motivates people, what inspires them, what determines if a person can enter a state of flow or is just standing still. Also, the strategic game; how would my competitor interpret it if I move in that direction, what would their response be, and is there a way for me to deflect; so the “chess” aspect of it, or the chequers aspect – whichever you may prefer. I completely shifted from financial economics in the beginning, to focusing more on strategy, management, organisational behavior, leadership. I find it truly fascinating, because in human relationships, under all conditions, you always have to perform – a corporate setting is just an extreme case where behavior is pushed to the boundaries in order to secure success.

So, when I try out my ideas, I try them out on the only organization I know – which is my family. I am a simple guy who likes to work on the level of two people. If I can’t get an idea or concept to work on the level of two people, I don’t think we should expect it to work on the level of 10 people, 20 people, 20,000 people. At the end of the day, I think we should start working on the smallest level of analysis and then hopefully, we can scale. I find it very difficult to start thinking along the lines of how to organize 20,000 people; I like starting with two. Two is difficult enough – something obvious to anyone who has ever tried living together with another person! Two, is a good starting-point, I think.

And that’s my story of how I got into business. By not deciding.

My first public speaking experiences were during my military service. It was mandatory for all men aged 19 at the time. In order to avoid too much time in the woods (it is very cold in Sweden, and I didn’t want to sleep in tents!), I decided to get elected to every committee there was. We even had our own military parliament. I decided to get elected to go to the annual meeting of that. I was very shy and still am very shy. When I was young, I always blushed while giving a presentation. During that year, however, I sort of realised though that I had a natural talent for public speaking; for some odd reason, I sound very convincing, it seems! I don’t really know why that is. And, perhaps as important, I love it!

If you spend a lot of time in the academic trenches, the closest you’ll get to positive feedback is the absence of negative feedback. If you are giving a presentation and people are extremely quiet, that’s the best thing you can hope for. Because typically, they would go, “this was good, but” and then you get 20 minutes of negative feedback. I’m not sure if this is restricted to the world of academia though; I think you also find a lot of companies in which these processes are alive and well, unfortunately. When I started to do my funky gigs (presentations), you could see that people were happy; they were applauding, they were laughing, they were coming up to me afterwards to say, “I feel a little bit smarter now. You have made something happen to thoughts that I have had in my head for some time and now I know what to do about them.” And people were following up after a couple of months to tell me, “not only did you help me with my ideas; after listening to you, I was a little bit more courageous, so I went to my boss and I made this suggestion that I had been thinking about for the last year or so but hadn’t had the guts before.” That certainly made a difference to me.

At times, I do get stage fright with smaller gatherings of people that I know and really care about; at a friend’s wedding, for example, or at my son’s graduation party.

And of course, I did have stage fright the first time I did a presentation in front of 6000 or 7000 people, I didn’t really have a reference point. I mean, if 6000 people turn against you, you know you don’t stand a chance! Stage fright still happens occasionally, but it is completely random; it doesn’t have anything to do with anything that I’ve been able to figure out, but it is also very rare these days.

Think about it – what’s the worst thing that can happen? The worst they can do is tell you that you suck! It’s not like anyone’s going to kill you or harm your kids – the stuff that really matters in life!