Change-making and Community-building in South Africa

by Swara Shukla · Published · Updated

When The Cat and I sat down to brainstorm content for Women’s Day, my blue-clad friend (I can officially use that word now; refer to the previous article) was quick to point out something it seemed to have noticed while (creepily) peeking over my shoulder at my laptop during one of my idle Facebook scrolling sessions (although I prefer the term “snack breaks”). There is a new segment these days on the news feed for suggestions to follow; what caught The Cat’s eye (and mine too) was the fact that all the suggested pages were of women in influential positions.

“Making a difference” for me is a gender-neutral term, because for me it is always about the cause at the core. Although we were planning for a Women’s Day feature – my line of thought from that Facebook section was more “oh look how everyone in the suggested list happens to be really accomplished women!” (Fine, those were The Cat’s words too, I do give due credits.) It was such a seemingly trivial thing and I could have easily glossed over it like I do with most of Facebook’s adverts and suggestions. But the reason it caught my (our) eye was because it wasn’t Facebook blaring out “look at all these brilliant women you should follow” – it was just another suggestion section. In its own microcosmic way, it planted the seeds of inclusivity.

Cutting a long story short, for a Women’s Day feature, I (we) spoke to two changemakers who have committed their lives to tackling social issues in rural communities within South Africa; and yes, both of them happen to be women. As it turns out, however, the female collectives in South Africa are some of the strongest and loudest voices I have ever heard of.

Here are excerpts from what was a very inspiring Skype conversation. The Cat, being uncharacteristically considerate, “delegated” this one to me for some female bonding in the spirit of the occasion.

Rozanne Hay has worked with charities from the age of 10. Having grown up in a rural South African medical mission community, serving society is ingrained into who she is. “It takes a good amount of self-care to empower and care for others in their own lives. My priority remains my own family and four children, as they are the next generation.”

When I tell her I am doing an article for Women’s Day, she gushes about how women in South Africa make for such strong communities. “We are all vulnerable and need validation. The bond between women is a unique one. The ability to communicate compassion, understanding and the ability to transfer ourselves to another person’s set of circumstances and challenges and feel their load without uttering a word is something profound. The network amongst women in rural South Africa is very strong – they keep everything together, work extremely hard. The men are lazy.” She addresses her friend, as I turn to the left-hand section of my split Skype screen. “Julie, would you agree?”

“Absolutely! The men are used to sitting and drinking beer while women tend to the fields. In the banking system they have what they call a stokvel where the women get together and save collectively. If a child needs a school uniform, those funds are used to purchase the child a uniform and you can have a stokvel for grocery-shopping, or other community or personal needs. Often, they say a child is not raised by the mother here, it’s raised by a village, and a village of women at that. Everyone’s an auntie or a sister or a mother. It’s a very shared load and I think we can learn a lot from them. They are collaborative not competitive.”

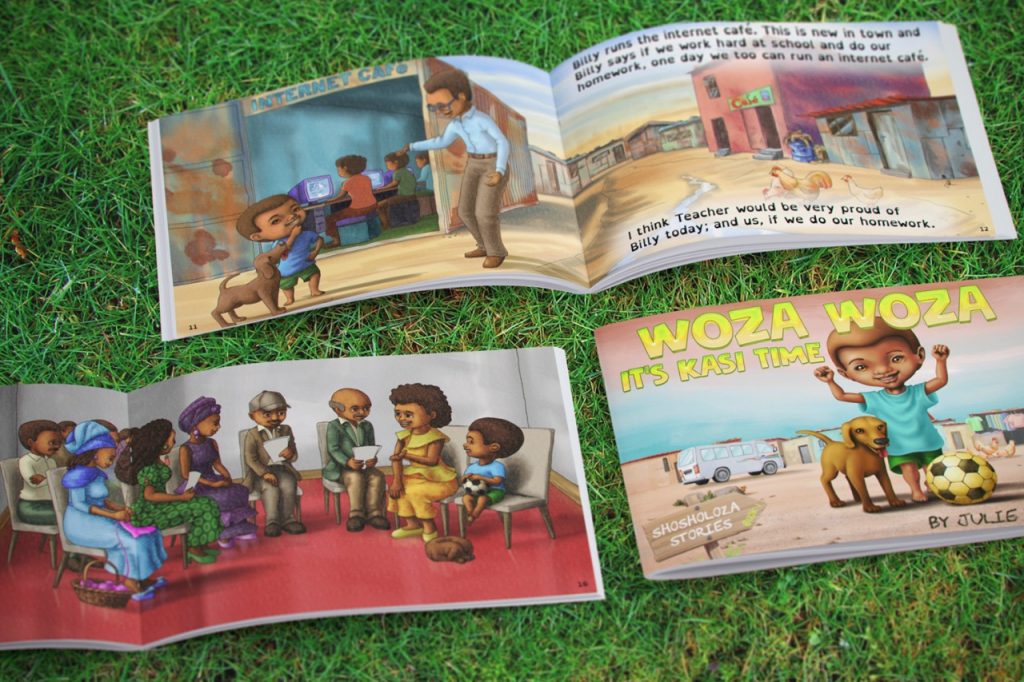

Julie Dakers is an entrepreneur and children’s author, who uses storytelling to reach out to children, promote education within the community, and encourage social entrepreneurship. “I had all this information in my mind having taught adults for the past decade and wanted to find a way to make the knowledge accessible to children. Travelling through these communities, I take local content and stories when I engage with people and write stories on the lives of those who live and work in these communities. They have a story to tell. It’s far more important than anything I could say. Hopefully through that, I can inspire the central theme of entrepreneurship and continued education. Knowledge is power at the end of the day!”

I tell them they should collaborate too; their dynamic is such a delight to watch. They laugh for a bit and discuss the prospect semi-seriously, with Julie settling on writing a book together because Rozanne is “a wealth of information”. Delightful, I tell you. Talk about female kindred spirits.

Children enjoying late-summer rains!

“It’s just a large bowl of energy!” Julie beams at me as I ask them what South Africa is like. “It’s a rainbow nation encompassing many people, many cultures, and much diversity. It’s a very exciting place to be in. There’s a lot happening, lot of hustling. I never know what’s going to happen the next day. Females are coming to the fore with entrepreneurship. They are also hitting up the households, but are not as subservient as they were forced to be in the past. There is a lot more gender equality and a really exciting space to watch. A lot is happening.”

Rozanne is settled in England and travels back and forth between the two countries. On what South Africa means to her, she says: “Mine is more sensory based. It’s definitely about the sights and smells. I think there are certain senses that have really shaped the way I have moved ahead in the line of work I am in at the moment. It is just that connection with intuition that I think we’ve lost in the West. The social landscape makes them [in South Africa] quite resilient and quite focused. The contrast of extreme existences – comparing those with everything and those with nothing – has been an enriching and insightful privilege and continues to inspire my journey.”

A medical train visiting rural areas in South Africa

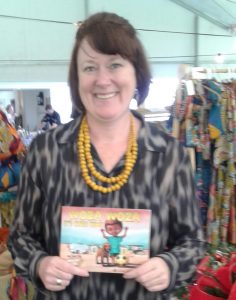

Julie at the launch of her children’s book, “Woza Woza”

I am curious about their work and how they interact with the communities there to bring about a change. Julie begins: “Most of my work has been in the last ten years. I have worked with a lot of communities around South Africa, and focused really on skills development; setting up business development centres to teach business skills. I got a little bit worn out in the corporate world so set up my own business last year about June, and have been writing children’s books. I take all the knowledge acquired having spent so much time in all the communities; and when I say communities, I am being diplomatic. I am referring to what we used to call townships. Very rural locations in South Africa. So spaces with very poor education, very disadvantaged backgrounds, and just trying to upscale the people there.”

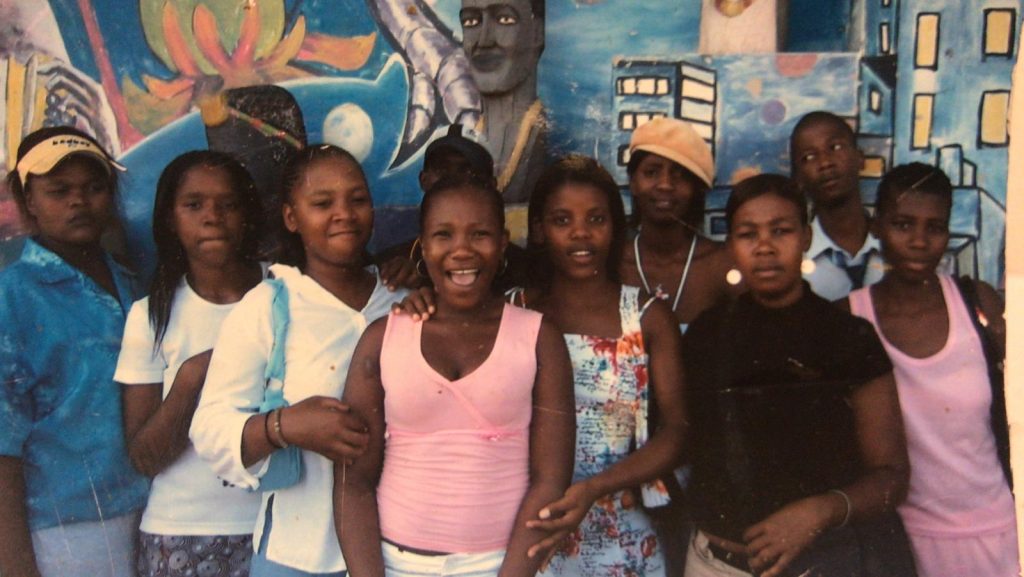

Rozanne joins in. “I have worked with aid agencies rehabilitating young women from 9-18 years of age who sell their bodies in an attempt to bring hope into their lives. There is a distinct difference between those that choose this form of existence and the vulnerable who need to exist. It is those whose basic needs aren’t met that I’m referring to. And they are some of the most vulnerable, soulful, beautiful women I have had the privilege of knowing. They have endured the toughest ride and dealt with challenging life events that no child should ever have to face; and it is through adversity that a soul flourishes. Wisdom is the upshot which shapes our values.”

All smiles while preparing for a community-event teaching flower arrangement skills.

I am sure I am echoing The Cat’s thoughts when I ask them to share some anecdotes or stories from there.

Julie recalls. “I was teaching a class, young boy – 23, 24 – you can’t always tell. He came to the class and was very disruptive. Frustrated, rude, unruly. The second day, there was a group of women – call them the matriarchs – that came in without being asked. He was barefoot, so they brought him a shirt, a pair of pants, and boots. It turned out he had absolutely nothing and his pride was impacted. He was acting out so that people wouldn’t stare at him, without realising he was creating so much negative energy that we were all staring at him. But the minute he got all the clothing – and they were all hand-me-downs, nothing fancy – he sat up taller, he became more responsible, helpful, with a great sense of pride. It was amazing to see these elderly women caring for him and nurturing him the way he needed. Another day, the ladies got together and chipped in and baked food; some of the students in the class hadn’t eaten. These are people who don’t have anything but the little they do, they want to share with 30 other people in the classroom – it is all quite overwhelming. You go in with your stereotypes in mind about poverty and how people behave. But they didn’t display any poverty or hoarding, they just shared freely. That’s beautiful, I think.”

Rozanne adds: “There are so many anecdotal stories I can think of, but sometimes it is just a tiny moment that makes you think. Last week, there were some children running around with their mother and I asked them why they weren’t in school. And their mother replied telling me their textbooks were wet, so that would actually prevent them from going to school. It’s just little things like that; their homes aren’t insulated from the weather, and things like these would actually prevent them from being in school. The teachers are strict, the schools are strict. They do need to have a uniform, and they do need to have dry textbooks. There are all these aspects as well. You have some elements against you, you don’t get access to education. Which is why it’s poor quality education. Funds are a bit limited because they can’t accommodate all these variables.”

Julie says about her book: “It must be inclusive to all children. Teenagers or children you would call privileged also love reading authentic African stories.”

As the conversation moves towards the differences between the rural and urban spaces in South Africa, Rozanne mentions how it must be similar to what I see in India. Having seen two extremes myself – one of the shared cultural facets comes forth in the form of how community-based these spaces are. Poverty-stricken rural areas, both in South Africa and India, are often characterized by a cohesive familial/communal unit as a means for basic survival and support.

Rozanne agrees. “[The community] is the focus, a common purpose for everybody. They work like clockwork. It is quite interesting to see. I think that’s what a happy person is, a person in a safe environment and a network of support. What do you think Julie?”

“I agree, yes,” Julie responds. “There’s a saying here, and I believe very strongly in it; it’s the belief of the ubuntu. It means I am because you are. In essence, the philosophy is that I am because of all of us. So, there’s nothing about one selecting oneself or having a strong ego. The belief is you exist because of everybody else, so we are all in it together. It’s very much about getting on with things so you see it in entrepreneurial spaces; no one wants to stand out and be special. It is great in one aspect, and on the other hand, one would think – if you have the qualifications and the natural ability going for you to excel, it’s not welcome. So, there’s the other side of it too. There are pros and cons.”

And what about an “urban fantasy” in the rural areas? I am curious to know if it exists there too. Rozanne presents a harrowing story.

“[Migrating to the cities] is seen as the successful thing to do, But they get exploited.

So many stories here. Generally, the scenarios we come across involve very young girls. They move to the city because their mothers would move to the city. There would be an older child – nine to eleven years of age – looking after the younger one who is two or three, while the mother goes out to work. One day, the mother doesn’t return. The child doesn’t know what to do, doesn’t know how to feed the little one. She starts asking neighbours for help. No one knows anything. It is through those types of circumstances that these children are failed in the communities. There is no support network or social network. No one is taking note of the neighbour’s children whereas they would know in the country. Everyone would know what might have happened or what was going on. In a week or two – there will be an ill hungry baby, and eventually a sex worker of a similar age will tell her how she can earn 50 rands – which would be about 3 pounds, I think – and that’s how she gets into prostitution. It is survival. Along the way, the child in her ends up dying. It’s all driven by absolute desperation.

You’ve got communities, especially along the north area. You’ve got some unity there, so you’ve got all these young girls taking turns to look after the children. Some are their own children, some are results of their clients. But they’ll take turns to look after a child while the mother’s gone out to make more money. They live under a few holey sheets supported by iron and sticks and cardboard-boxes. They are just existing. They have gone through so much.

Once one of them managed to get a lift down to a radio station – she was 13 at the time, I think – and just asked ‘do you know who I am’ on air. Some relatives from miles away claimed her.”

Julie adds: “There are lots of neighbouring countries who are probably worse off than South Africa. I have worked with quite a few ladies in Johannesburg who were given the promise of crossing the border and being able to get a better life. They ended up in prostitution out of sheer survival. The young girls have nothing. It is so heartbreaking. We do try to rehabilitate by teaching them secretarial skills, administrative skills – getting some kind of donor funding in to help them get on their feet. Sometimes the lucky ones – if we can even use that word – get to go back home.”

“Yes.” Rozanne responds. “As regards to the rehabilitation programme – we literally used to go out in the evenings, and just identify people at risk. And we then offered a six-month counselling programme. Many of them are too young to be able to do much, to be honest. We try to teach skill-development These skills – be it beading or sewing or whatever else – are very therapeutic for them. It gives them an opportunity to talk through everything and it is really interesting. Often, no one would have spoken or said anything for two hours, and then someone would start something and somebody else would add to it. And before those 2-3 hours are up, I would just wish they would stay and carry on, because what was happening was so rich, so extraordinary. You see the human soul and how it deals with such adversity. How resilient it is and is able to pull through and be there for each other. It’s really interesting.”

A women’s support group on an excursion to the national newspaper.

Copyright of all pictures lies with Rozanne and Julie. All photographs have been published with due consent from concerned parties.